Tucked away in the back of Texas A&M-RELLIS is a nondescript building that houses some of the most exciting and innovative robotics research at Texas A&M University. Everything from a Robonaut to a giant rolling RoboBall can be found in Dr. Robert Ambrose’s Robotics and Automation Design (RAD) Lab. Because at Texas A&M, the sky’s literally the limit in what he and his students can design.

Before joining Texas A&M, Ambrose spent decades at NASA’s Johnson Space Center. There, he was the chief of the Software, Robotics and Simulation Division, where he led the development of advanced robotic systems for space missions.

He retired from NASA in 2021, and later that same year, he joined Texas A&M. With him, he brought decades of experience in robotics, an impressive work portfolio and boundless enthusiasm for creating innovative prototypes.

“I’ve always enjoyed prototyping,” Ambrose said. “Going back to when I was a kid, I was always designing and building things.” At NASA, he led projects like the Robonaut, a humanoid robot designed to assist astronauts, as well as various rovers and exoskeletons.

“I really enjoyed prototyping new ideas, and the first branch that I led was kind of the technology branch that developed new prototypes. I was teaching the young engineers and old engineers just how to do prototyping, to think about a problem, try different ideas and to rapidly do that, where you weren’t taking years to come up with a solution.

“I found A&M had a hunger for that and this idea of mixing research engineers and grad students together. And I knew a little bit about that and said, ‘OK, I think this is going to be a good place for me.’”

And it has been a very good place for him. Today, he holds the J. Mike Walker ‘66 Department of Mechanical Engineering endowed chair and is a University Distinguished Professor. He is also a member of the National Academy of Engineering and has received several NASA medals for his work in advancing robotics.

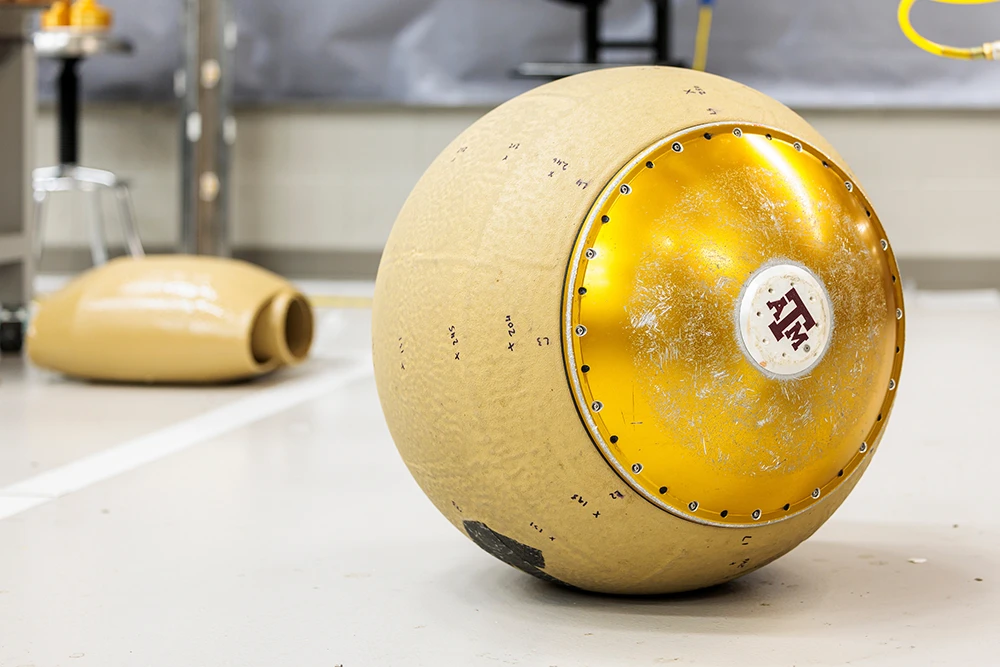

Ambrose has continued his innovative research at Texas A&M, focusing on space robotics and autonomous systems. Some of his current projects include the RoboBall, a spherical mobile robot designed for missions in challenging environments like the moon or post-disaster areas on Earth.

But one of the things he’s most excited about isn’t the prototypes and research — it’s working with the young research engineers and graduate students eager to push the boundaries of what is possible in engineering and robotics.

Photos by Abbey Santoro/Texas A&M University Division of Marketing & Communications

Building a Better Robot

In 2022, Ambrose started the RAD Lab with five graduate students. Today, the lab has 31 staff members, including research engineers and graduate students. The lab’s mission is to “design and deploy resilient robots tailored for harsh terrestrial and extraterrestrial environments, while fostering safe exploration and collaboration between humans and robots. We will cultivate the next generation of engineers, guiding them to usher in the next chapter of robotics.”

The robots being designed in the lab aren’t just there to look cool — they serve real-world functions. There are projects like Marsupial, a robotic deployment system that can release smaller, specialized robots. The smaller robots can perform manipulation tasks, survey enemy territory, navigate smaller passageways and are interchangeable depending on the mission needs.

Another project, called Rover Rescue, is geared toward space applications, primarily for preventing rovers from getting stuck in difficult locations. With Rover Rescue, if this happens, another robot with a robotic arm can hook a tether on a winch and pull it out of its rut.

And these innovations are all happening at the RAD Lab. Much of the ideation and implementation is being conducted by young research engineers and graduate students under Ambrose’s oversight.

“We have a bunch of teams led by a variety of students and full-time engineers working on various projects, including mobile robots, robotic manipulators and others,” said Vidur Zimmerman, a research engineer in the RAD Lab. “We really have a good team here, where it’s a mix of grad students and engineers. It’s a one-to-one ratio, so we really have the opportunity here to collaborate and work toward those long-term goals and projects.”

As he was building his team, Ambrose knew that character was as important as the skill sets the employees could bring to the table. “My dad used to tell me, ‘You can coach everything except probably character.’” That stuck with Ambrose.

“I’m looking for character in the employees,” he said. “We’ve only hired people that I think are really good people. And it turns out that’s pretty easy at A&M. We have an amazing kind of person that comes to A&M. Finding people that can work with others and that like what they’re doing and that are kind and good teammates, good citizens, those are the kinds of things that matter.”

Photos by Abbey Santoro/Texas A&M University Division of Marketing & Communications

“It’s a community of engineers who are trying to make this world a better place. I really love the culture we’ve fostered here at the RAD Lab. We have such a great community of people. I think something that I see here that’s not really common in a lot of research labs is the extent of the collaboration. We’re really all open to learning,” Zimmerman said.

“I see this lab as a force for good because a lot of our projects are serving potential U.S. needs,” Zimmerman added. “So, I think where we need to focus is on our terrestrial robot design that we hope to make extraterrestrial, because of our needs in space applications, military and in general.”

Ambrose is also the associate director of the new Texas A&M Space Institute, which will serve as a testing ground for some of his lab’s robots, like RoboBall and some of the rovers.

“The Marsscape and moonscape will allow us to test our rovers, or some of our other mobile robots, like our RoboBall. It’ll be a great environment for us to test those mobile robots and other things, while we still do a lot of our prototyping here,” Zimmerman said.

Immersive Learning Environment

Ambrose’s lab is almost entirely run by students, which is by design. He was inspired by a biography of Neil Armstrong, reading about the astronaut’s surprise at the age of the employees at Johnson Space Center. “He was shocked when he showed up. He expected a bunch of gray beards walking around. No, it was a very young team. No one else had ever done it before. And they figured out how to do it. It was a young team that took the first man to the moon. I will never forget that, just reading that in his biography. And so maybe we can keep doing that.”

Ambrose said that young students today have opportunities once only reserved for mid-career employees. “They’ve got much more responsibility. They build stuff. They test stuff. They work together in teams. And they’re doing things that professionals used to do more, like in the middle of their career, back when I was their age. And a lot of that is just the way we’ve built the team. But it’s also a change in the field of robotics. So we’re at an amazing moment in robotics where students today are doing things that used to not be possible except with large teams.”

Photos by Abbey Santoro/Texas A&M University Division of Marketing & Communications

Stephen Hester, a mechanical engineering doctoral student, is working on projects in the RAD Lab that many engineers may not have the chance to work on until later in their careers. But under Ambrose, he’s collaborating on highly complex projects. He says working with someone of Ambrose’s caliber can be a little intimidating — but extremely rewarding. Even when things go wrong.

“Any time a robot breaks or something doesn’t work, it’s a learning opportunity. And the way we approach problems in the lab is, ‘OK, stop. What did we learn from this?’ It’s not, ‘Oh, no, everything’s wrong, everything’s bad.’ Pause. Think about this. What can we learn from this? What can we improve?”

We’re at an amazing moment in robotics where students today are doing things that used to not be possible except with large teams.

Ambrose has built a collaborative community in the RAD Lab, one where grad students and undergraduates work with researchers and engineers, all working together toward a common goal: to create something amazing.

“All the stuff we do would not be possible without Dr. Ambrose. His passion and his leadership and his need to keep training new people are the things that I love about the lab. We’re trying to never be stagnant and never only have the same group. We’re always trying to bring in new people to work with and to learn from,” Hester said.

“I think what really inspired me was his dedication to building really good engineers, like building people up, not just robots,” said mechanical engineering doctoral student Sarah Lam. “So he told me his vision of how he wanted me to leave this program: ‘I’m going to get you a job. I’m going to connect you with people. You’re going to come out as a legit engineer.’ So I think his vision for building people up and the care that he’s put into finding my interest and finding projects that fit within my interest was something I thought was really inspiring and kind of attracted me to this lab,” Lam said.

Photos by Abbey Santoro/Texas A&M University Division of Marketing & Communications

Inspiring the Next Generation

Every summer, Ambrose’s lab hosts 30-40 undergraduates for the RAD Lab Summer Program. The 10-week internship program attracts students from all over the U.S.

“They spend the whole summer working with grad students and professional research engineers. And I’ve noticed a few things,” Ambrose said. One of those is how the students react to seeing students not too much older than themselves, doing high-tech work in the lab. “They can picture themselves leading a team as a grad student. And it’s changed their lives. It’s changing their career trajectory. It’s exposing them to this idea of prototyping and designing and building. And that approach of quickly designing and building is exactly what industry needs right now for creating new projects. You’ve got to be able to think fast and get a quick testable product that can be evaluated. And then you learn from it and rinse and repeat. That’s what we’re teaching here.

“The grad students are going to be world-class experts at it after they’ve been doing it for, you know, three or four years in grad school. They’re already teaching me how to do it better.”