Each May, Karoni Forrester ’96 packs her bags and heads to California to join her fellow Run For The Wall riders on the annual 10-day trip to Washington, D.C. She doesn’t ride because she’s a motorcycle enthusiast — even though she has made this same trip for 15 years — she rides to honor and bring awareness to those who are still listed as missing in action (MIA).

“It’s a four-pronged mission, and it started with promoting veterans’ healing. The second was to call for the accounting of our POWs and MIAs, to honor the fallen from all wars and to support our active-duty military worldwide. The thing that got me involved was the POW/MIA part, not the motorcycle part.”

It’s a demanding 2,600-mile journey across the U.S., but it’s one filled with purpose, pride and personal connections.

Forrester remembers a man approaching her on one of her first rides and asking her what it was like to be a Gold Star daughter. Gold Star families are those whose loved ones died in active-duty military service. She was a little taken aback by what she considered to be a rather bold question.

But she thought about it, and while MIA families are officially considered Gold Star families, she replied that she didn’t consider herself a Gold Star. “I’m an MIA daughter, and I’ll take a gold star when they find my dad.”

He then asked what color star an MIA family has. “I said, we don’t have a star. And he just stared at me and said, ‘What is the color of hope?”

She said she didn’t know, but she liked the way he was thinking.

“The next morning, he came by the bike when we were getting ready to leave. He said, ‘The color of hope is green.’ So, you’ll see in our pictures that we have a green star. That’s our outreach pin that we give to people who participate.

“We wear green hats and represent our outreach as hope: hope for answers for those who are still missing, and also hope for healing for all of our Gold Star families who lost someone in service.”

Found Family, Shared Grief

Capt. Ron Forrester ’69 was declared MIA in Vietnam after he and pilot Capt. Jim Chipman didn’t return to base after a bombing mission on Dec. 27, 1972. It took more than 50 years for the Forrester family to get answers when his remains were finally identified in 2023.

The years in between were filled with grief and a longing for answers. Answers that didn’t come.

“Growing up, there was not a time I remember not asking where Dad was. And the thing is, no one knew how to answer that question, so it was a ‘Well, we don’t know. We’re waiting to find out.’”

The lack of answers just created more questions for Forrester, as well as the fear of what her father was going through. “I was very tormented with all of the things that could have happened to him. Did he die in that incident? Did he die in prison? What happened after that plane was shot down? Did he feel forgotten by his family? Did he feel forgotten by me?”

There were no answers to those questions, but as a teenager, Forrester found there were people like her going through the same pain as she and her family. It was a community built on grief and hope.

Karoni Forrester ’96 was only 2 years old when her father, Capt. Ronald Forrester ’69, went missing during a mission over North Vietnam on Dec. 27, 1972.

“When you’re growing up, and you’re looking for people to identify with, that just wasn’t an experience that was commonly shared. I was 14 when I first met other MIA family members, and that was a big game changer for me to realize that there was this community, and there were also just very concerned citizens who were working in the POW accounting mission.”

Forrester later channeled her grief and energy into action by becoming an advocate for POW/MIA veterans and their families.

“I believe in answers, and I know the power they hold, the peace they bring. And it’s important that these families feel supported while they continue to demand answers, as they continue to walk this lonely road.”

Four Routes, One Mission

Fifteen years ago, Forrester took part in her first ride with Run For The Wall. The Run is held every May to honor veterans, their families and friends, and to raise awareness of those still missing. The ride kicks off in Ontario, California, and ends in Washington, D.C., at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall for Memorial Day weekend.

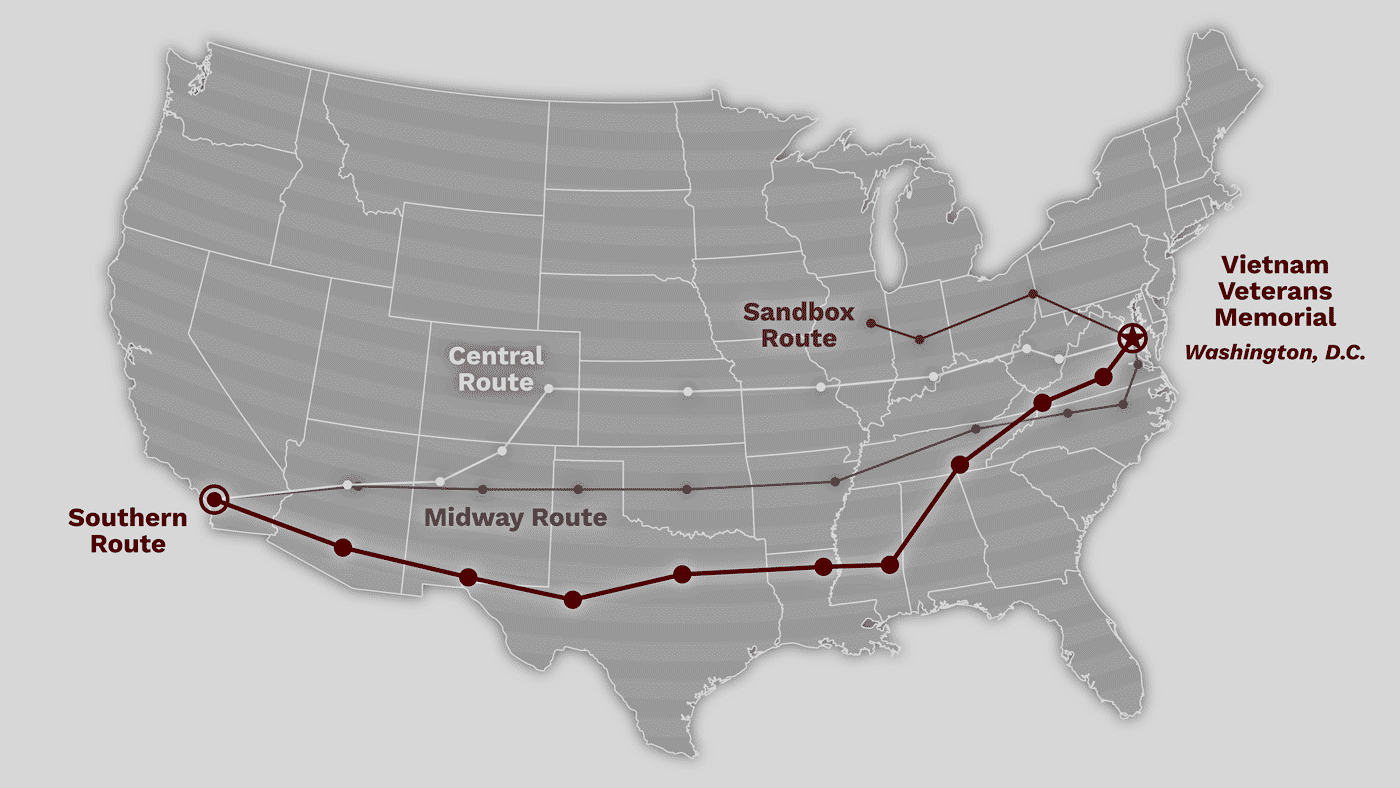

There are four routes, with three starting in Ontario and then branching out into different tracks to D.C.: the Central, Midway and Southern. All end on the same day, with riders meeting up at the Vietnam Memorial. Forrester takes the Southern Route, which winds through Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Tennessee, Virginia and finally, D.C.

The fourth route, called the “Sandbox,” is much shorter than the other three, leaving D.C. on the Sunday of Memorial Day weekend, headed toward the Middle East Conflicts Wall in Marseilles, Illinois.

Forrester takes the Southern Route, which starts in Ontario, California, and winds through eight states. The riders from all of the routes meet up at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall in Washington, D.C., for Memorial Day weekend.

She first learned about the ride while she was in Cupertino, California, on business, when some friends took her to a local American Legion. There, she met an older Marine who asked her if she’d heard of Run For The Wall and if he could carry her dad’s photo on his motorcycle from California to D.C. She agreed.

A week later, he reached out again and asked her if she could put together some photos and bios for the ride. “You’ve got a lot of MIAs; I’ve got a lot of motorcycles. How many different bios can you get me?”

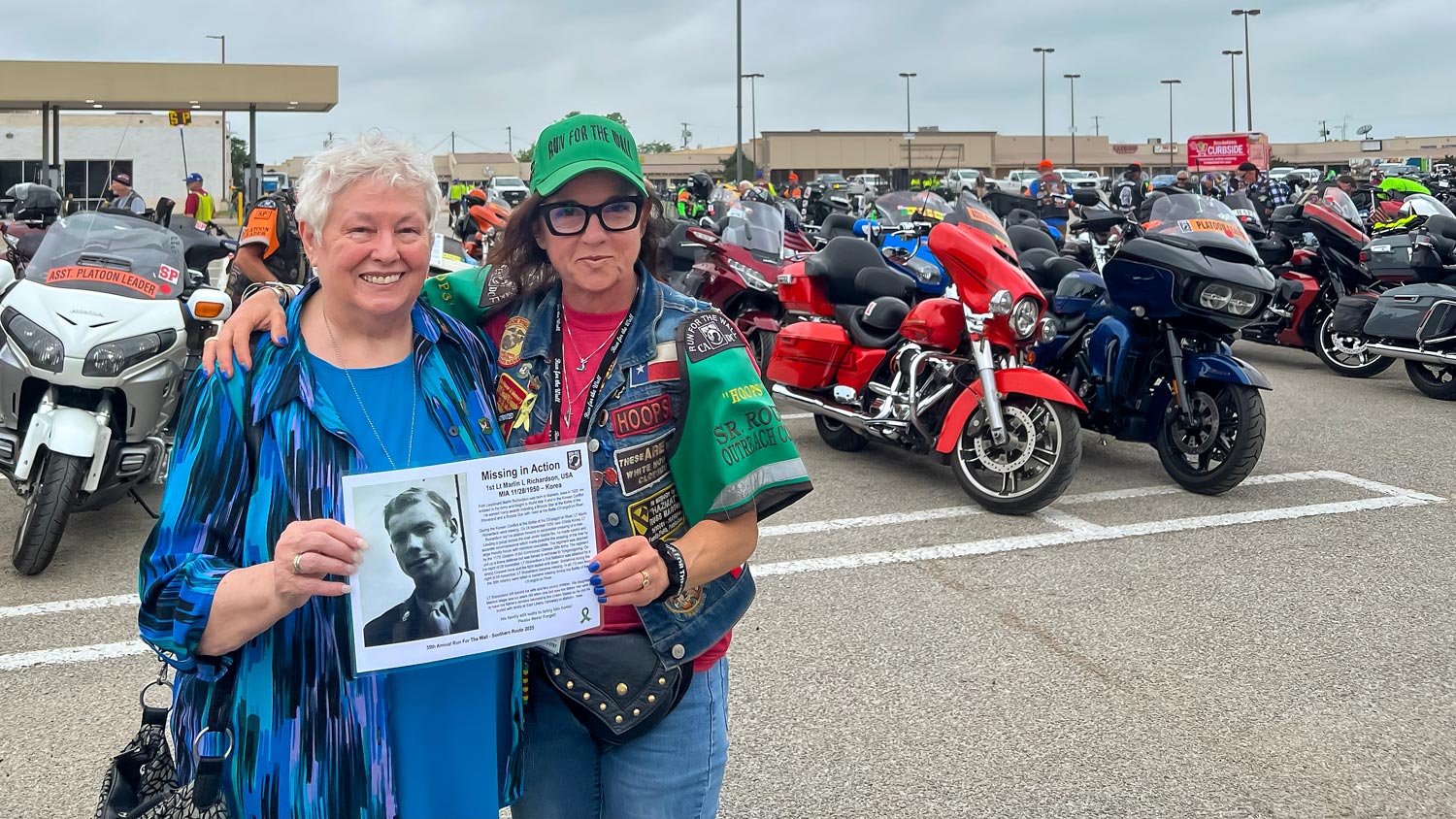

That year, she gathered 50. Today, she has about 200. Displayed on bikes during stops, these profiles bring names, faces and stories to those missing. At the end of the ride, they are placed against the memorial wall. Forrester and her family reproduce the bios each year for the next Run For The Wall mission.

Although she was a little hesitant at first about riding a bike across the U.S., she decided to give it a try. She’s quick to add that she rides on the back of the bike during the long trip and isn’t in charge of the handlebars, because sometimes she likes to nap. Today, she’s still going strong with the group, talking to people along the way, listening to their stories and sharing her own.

“I met a man in New Mexico in a parking lot, whose brother is MIA. He’d been standing outside watching all the bikes come in with Run For The Wall, and we brought him inside and sat down and talked with him. I was telling him how he’s not alone, and his tears came down his face. He said, ‘Sometimes it really feels that way.’ I know it does, but it shouldn’t,” she said.

Forrester says a big part of the ride for her is to let veterans and their families know they aren’t forgotten. “We go and embrace different MIA families and Gold Star families along the way because I know that if somebody came to my house and said, ‘Your dad’s not forgotten,’ that would have meant a lot to me. So, I love that I get to do that for other families.”

At the end of the 2025 ride, Forrester visited her father’s grave in Arlington National Cemetery.

Connected by Grief and Hope

The ride takes 10 days from California to D.C. But that’s just part of the time participants spend on the ride. “These people are giving up their vacation time to work this mission and raise awareness for our loved ones,” Forrester said. “I wanted as many MIA families to see it as possible, so I started inviting people to come to our stops.”

Riders make stops along their routes to meet with people and share stories about what they’re doing and those they honor. But they stray very little from the route … that is, until Forrester talked to a friend and MIA sister, Jo Anne, in Dalton, Georgia, about her mother, who would love to see the riders.

One problem — her mother was in her mid-90s at the time and living in an assisted living facility, and there was no way she could make it to the official stop in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Her friend asked if there was any way the riders could take a detour to visit.

Forrester, whose road name is “Hoops,” meets with families of MIA/POW soldiers during stops along the bike route. Each year, she and her family prepare bios that are displayed on bikes during these breaks. The profiles include the names, faces and stories of those still missing. At the end of the ride, they are placed against the memorial wall.

The following year, 20 riders went off-route to meet her. “We probably got to visit her five or six different times, and she’d say to her son-in-law, ‘Look at all my boyfriends.’ I mean, she’s just a riot,” Forrester said. “But you know, she’d get real quiet in that space when she talked about her son. And she’d say, ‘My boy, Bobby (Jones), wherever he is, I know he’s doing something good.’

“I think that she left a mark on all those riders. Anybody who got to go visit her went home with a story about why it was important for us to account for our missing, so while that was our very first inaugural outreach, now we break off multiple times throughout the route and visit not only MIA families but also go and honor our KIA (killed in action) families along the way too.

“We have a family in Louisiana whose loved one has been missing now for almost 59 years. There is some progress going on in that case, but through getting to do these outreaches and knowing them better, I’ve been able to actually be able to kind of give some coaching and guidance to them on, like be sure you ask these questions, push these different things when they’re having their conversations with the government. So, as much as we can, we have MIA families come visit us along the route, but if they can’t come to us, we go to them.

“We want to make sure that we’re telling the story that these people cannot be forgotten. Their sacrifice cannot be forgotten. And a saying that I really like is that we must live a life worthy of their sacrifice.”

Honoring Fallen Service Members on Memorial Day Weekend

After the official end of the 2025 ride, Forrester and her husband headed to Concord, North Carolina, to join her cousin Craig Forrester ’94 and his family to watch the Coca-Cola 600, a NASCAR Cup Series race, where her dad would be honored on the No. 41 Texas A&M Ford Mustang driven by Cole Custer.

Custer’s car was decked out in a special livery of Aggie Maroon complemented by camouflage in honor of the nation’s fallen military service members and signifying Texas A&M’s commitment to all military-affiliated individuals. Forrester’s name appeared on the windshield of the car during the race.

Forrester and her family attended the Coca-Cola 600 and met Cole Custer, who drove the No. 41 Texas A&M Ford Mustang. Her dad’s name was displayed on the windshield of Custer’s car during the race.

“It’s just so Aggie and awesome. I love that it had the POW/MIA logo on it because that’s a huge part of our story. But for him to be honored in such a fast, glorious way, I just know Dad was beaming and laughing.

“When I saw the car, I just wanted to run right over. It took my breath away. And it was a lot to process,” she said. “I’m so very grateful that Dad was honored in that way. It was just such an amazing honor for him. The support and love that we’ve received from A&M on so many levels just continues to really be a big fat hug for our family, and it feels really good.”

Home Away from Home in Aggieland

Although Forrester doesn’t remember her father, she still feels a connection to him, and one way she has kept that connection is through Texas A&M. She and Craig, whose father is Ron’s twin brother, both attended Texas A&M.

“The connection that I have to our school, and the connection he had to it, is actually a connection now that I get to share with him,” she said. “Daddy was the first Forrester to go to Texas A&M, but definitely not the last. I think my cousin and I both just felt like it made the most sense for us to go there. And, you know, looking back on it now, I think I definitely was seeking that connection with Dad, having no idea on what level that was going to happen and how very deeply rooted Texas A&M would be as part of a bond with me and my father.

“After Daddy was accounted for, as I was making plans for the celebration of life, and my brain was just moving on, what do I need to do for Dad? One thing that I really wanted to do for him again was with that connection with Texas A&M. I felt it would be important to have a scholarship in Daddy’s name to help somebody else in the Corps in financial need. I know how much Daddy loved Texas A&M and how much A&M impacted who he became and how it helped him find his dream in the Marine Corps of becoming an aviator.

Forrester feels a deep connection to her father through their shared bond as Aggies.

“Texas A&M really offered him a pathway to fulfill his personal dreams, and it’s become such a pathway for people in my family moving forward. And I didn’t want just something in a Forrester name. We know there are a lot of us.”

To make that a reality, Forrester, with strong support from the Class of ‘69, established an endowed scholarship in his name. The Capt. Ronald W. Forrester ’69 Endowed Scholarship through the Texas A&M Foundation will help students in the Corps of Cadets.

“I grew up in Odessa, Texas, but I feel like most of my growing up as a human being happened in Bryan-College Station at Texas A&M. I do very much feel like I’m going home as soon as I get on the outskirts of town. Aggieland is home.”