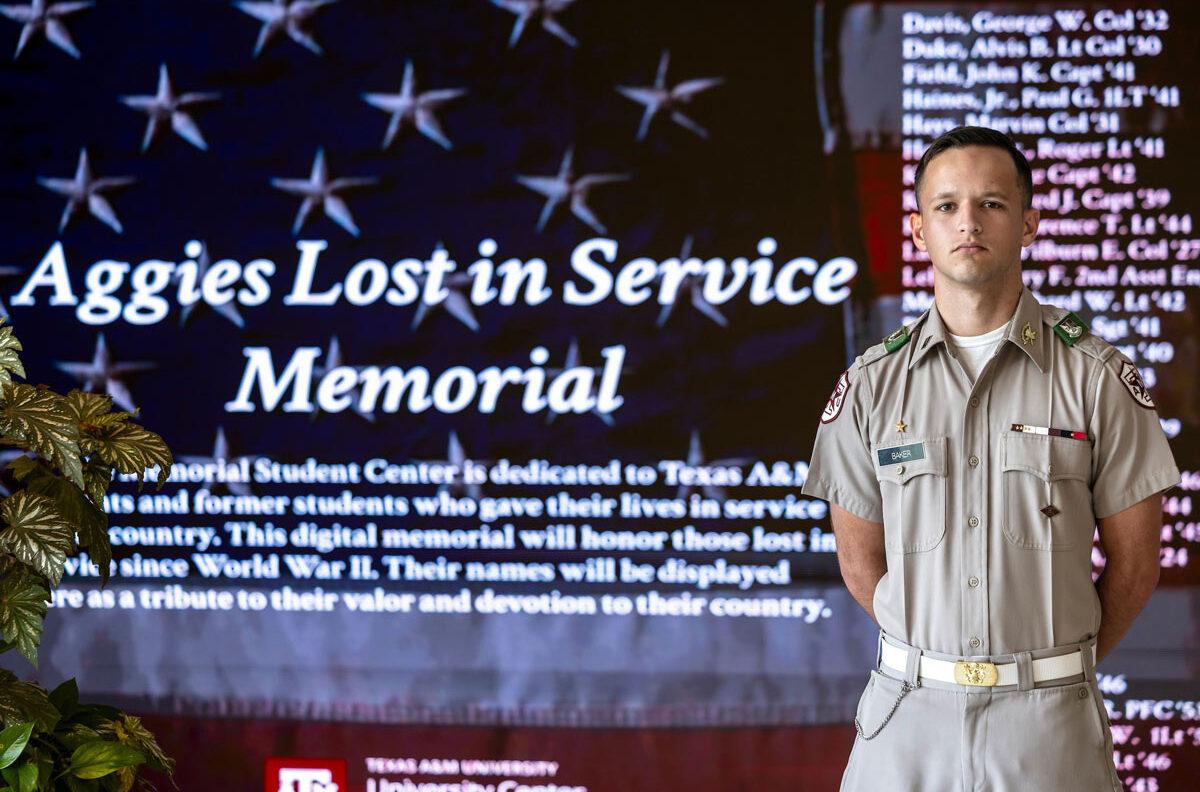

What was supposed to be a research project to track down and compile the names of Aggies missing in action since World War II turned into something else for Jackson Baker ’25. It became much more than listing out the names, class years and hometowns on a spreadsheet. It became about learning who these Aggies were and making sure they and their sacrifices were never forgotten.

“Softly call the Muster, let comrade answer, ‘Here’…” One of Texas A&M University’s most solemn and cherished traditions is Muster. Held every spring on April 21, Muster honors Aggies who have passed in the previous year, with friends and loved ones softly calling out, “Here,” when their loved one’s name is called.

Photos by Laura McKenzie and Abbey Santoro/Texas A&M University Division of Marketing & Communications

“I’ve always believed that Muster is a window into the soul of Aggieland,” President Mark A. Welsh III said during the 2025 ceremony in College Station. “It’s a spiritual homecoming that brings Aggies together across continents, across generations and across time. It reminds us that no Aggie is ever alone. And of course, more than anything else, Muster is a celebration of those Aggies who no longer walk beside us…”

Muster, at its core, is about remembrance. And remembering those we’ve lost and learning their stories takes work and dedication. It takes grit. And it takes a whole lot of Aggie Spirit.

Before embarking on this research project, Baker remembers hearing Welsh give the 2022 Muster speech and how much it impacted him and his friends who were in attendance. Listening to Welsh speak of honor, service and sacrifice, Baker said, “It’s that tradition that really grounds you at A&M and puts things into perspective. Even as students, we have a greater sense of duty to something greater out there.”

Gen. (Ret.) Mark A. Welsh III’s 2022 Muster speech had a meaningful impact on Baker and his friends.

During that speech, Welsh recalled the time when he lived in Germany and his wife, Betty, encouraged him to take their children Matt and Liz, then teenagers, to Normandy, France, on their Spring Break, “to see the beaches and the battlefields and to show them that holy ground, so they could learn and understand just a little bit of the experience that forged their grandfather into the incredibly special man he was,” Welsh said.

The trio visited many battle sites, including Omaha and Utah beaches, and cemeteries. They ended their visit at the Brittany American Cemetery, located outside of St. James, which is one of the smaller cemeteries where American soldiers were buried. “As we stood in that beautiful and haunting place with its perfectly aligned white crosses, I told Matt and Liz about the 4,410 Americans who were buried there. I pointed out the 20 sets of brothers who lay side by side for eternity. I showed them the 498 names on the wall, the missing, and reminded them that that meant 498 families who never recovered any part of their loved one.”

Search for the Missing

According to the U.S. Department of Defense, there are currently more than 80,000 Americans listed as missing in action, and the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA) is tasked to provide the fullest accounting to the families of the missing.

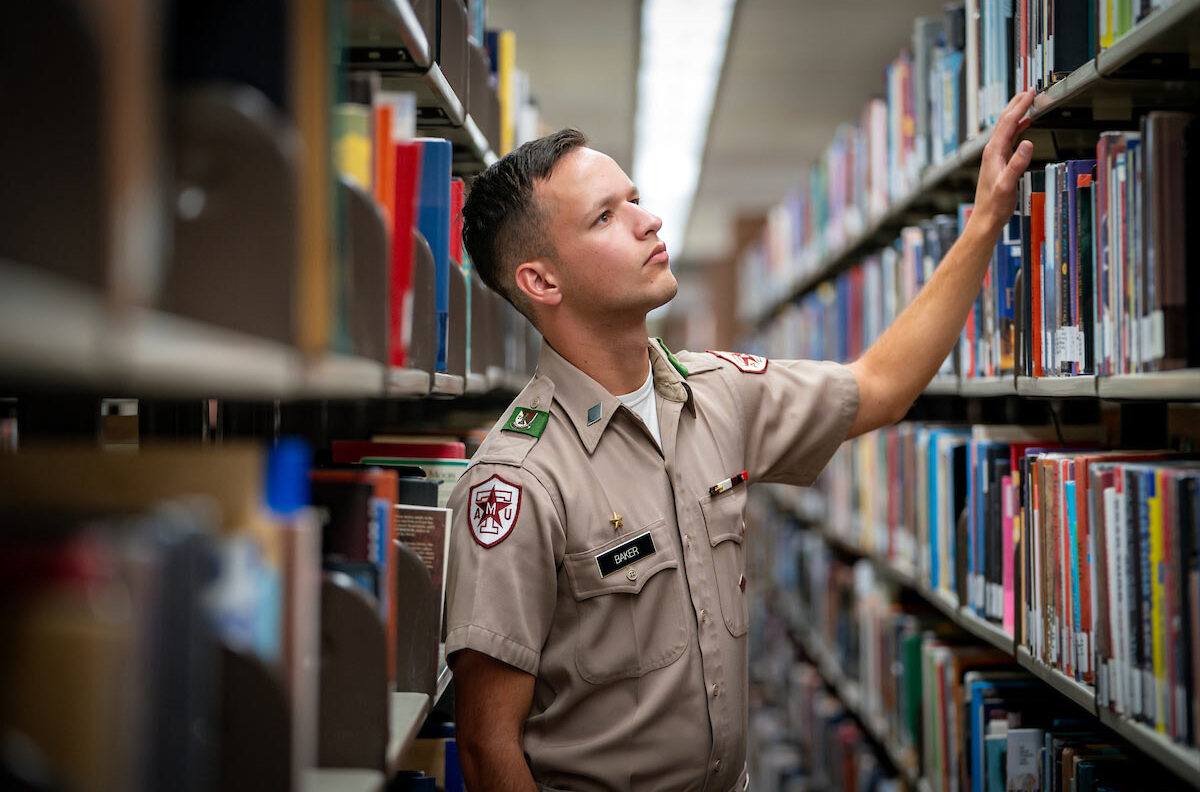

Baker, who graduated in May and plans to continue on to graduate school, joined Dr. Erika Bravo’s research group in 2022 as an intern. Bravo is a research partner fellow in the College of Arts and Sciences at Texas A&M who is conducting historical research in support of the DPAA. The DPAA had tasked Bravo’s team with finding photographs of Texans listed as missing in action to accompany their service member profiles on the DPAA website.

Since yearbooks are a great source for photos, Bravo asked Baker to start with Texas A&M’s Aggieland yearbooks first, since they had easy access to them, and look for photos they still needed. She also asked him to look for a list of Aggies unaccounted for and compare it to the list of photographs they still needed. He soon discovered that no such list existed, but he wanted to create one. This spawned the project and his undergraduate thesis.

Tracking down the missing Aggies turned Baker and his fellow interns into amateur sleuths, as they worked together to find out not only who these Aggies were — but what their stories were.

Photos by Laura McKenzie and Abbey Santoro/Texas A&M University Division of Marketing & Communications

“Once we had figured out a project and a need to produce a list of Aggies missing in action and to tell their story for the first time together, we submitted an application to launch the Undergraduate Research Scholars thesis program. The project was accepted in August of 2023, and that kind of became the whole basis of the history research internship. So everybody was contributing to that and finding information. And it became my job to kind of categorize that information,” Baker said.

He and the team started with a list from the DPAA of Texans missing in action, which they would in turn cross-check against material they had, including memorials, Texas Aggie publications and the “Find an Aggie” module on The Association of Former Students’ website, which Baker said was an incredibly valuable resource.

“One thing we noticed while looking through these different lists was the discrepancies between them. For example, The Texas Aggies Go to War book has about 850 names in the World War II killed in action section in the back of the book, and the memorial in the Memorial Student Center, the John 15:13 Memorial, has over 950 names.”

The research is really important for A&M. I think it’s really important to remember them as a whole, especially those missing in action and prisoners of war, especially for the families. These are Aggies who have not returned home yet. These are Aggies whose buddies have not been able to bury them.

During his research, Baker was struck by the connection the soldiers had not only to each other, but to the university and its traditions. From making bets on the outcome of a football game to the need to protect their Aggie Rings, the ties that bound these Aggies together were as strong then as they are today.

“The most incredible part of this research to me has been finding the connection that Aggies had, specifically in the prisoner of war camps in the Philippines during World War II,” Baker said.

He read the notebooks of Capt. Robley David Evans ’40, whose son, Judge David Evans ‘71, is also an Aggie. “One of the first things that is taken from him when he’s taken prisoner is that big old Aggie Ring,” Baker said. “And you know, before being taken on the Bataan Death March, he marched up to the Japanese commanding officer who had taken the ring and demanded its return.” Baker said that Evans was later beaten for his refusal to hand over his ring.

He found stories about other Aggies who went to great lengths to hide and protect their rings. Unlike many of his fellow soldiers, Evans survived his time in the Japanese POW camp, along with an estimated 33 of his fellow Aggies, and returned home after the war.

But not all Aggies came back. “A really important part of that military history is remembering our fallen, remembering what they did,” Baker said.

Finding the Lost Aggies

Baker said one of the goals of the project is to preserve the stories of these Aggies and share them with current Texas A&M students. “In the Corps of Cadets, the first thing they have you memorize as a freshman is John 15:13, ‘Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.’ And every night during freshman orientation week, we read a new Medal of Honor recipient story, one of the Aggies, and it really sets in your mind that you are part of something greater than yourself,” he said.

“The hope is that these names will be preserved for the future, those stories told, but that we can also fulfill that promise to the nation, that we will recover our missing,” Baker said.

“The goal with this project was to say, ‘Alright, here’s our list. Here’s where they’re missing. Here’s the story.’ Just kind of setting up a base of operations for the future. You know, even if we’re just tracking their recovery progress.”

Baker and the team have compiled a list of more than 200 Aggies missing in action. He hopes that one day Texas A&M will create a memorial in their honor.

One Aggie whose remains were recently recovered was U.S. Marine Corps Capt. Ronald Forrester ’69. After his plane crashed during a combat mission in North Vietnam in December 1972, he and Capt. Jim Chipman were listed as missing in action. In December 2023, the remains of both men were identified following DNA testing of teeth and bone fragments recovered during excavations of the crash site.

Friends and family had a celebration of life ceremony the following February, honoring his service, his legacy and his love for Texas A&M.

“One thing that really struck me when I went to the memorial service for Capt. Ronald Forrester was that his nephew was able to wear his senior boots when he was in the Corps of Cadets. But that was only on the stipulation that he kept them as shiny as he (Ronald) did every day. So anytime I’m a little tired and late for class, I think, ‘I have to shine those boots.’”

The hope is that these names will be preserved for the future, those stories told, but that we can also fulfill that promise to the nation, that we will recover our missing.

Baker is volunteering on an MIA recovery mission this summer with another DPAA partner institution. He said that he hopes that in the future, Texas A&M can be involved in recovering the MIA Aggies and possibly sending cadets on recovery missions.

“The research is really important for A&M. I think it’s really important to remember them as a whole, especially those missing in action and prisoners of war, especially for the families. These are Aggies who have not returned home yet. These are Aggies whose buddies have not been able to bury them.”

Keeping Their Memories Alive

Capt. William Mark Curtis ’32 was declared missing in action after the sinking of the Japanese “hell ship” Arisan Maru, on which he and 12 Aggies died. The Arisan Maru sank on Oct. 24, 1944, with Curtis and 1,773 other prisoners of war unaccounted for.

“What was really striking about that story is what his mother wrote about him after the war: ‘I feel that these men lived up to the highest American tradition of courage and ingenuity; they never quit, and they never lost their sense of humor. They have left a wonderful heritage for our children, and it is up to us to try to live up to their example and make their efforts worthwhile.’”

Photos by Laura McKenzie and Abbey Santoro/Texas A&M University Division of Marketing & Communications

To help keep their memories alive, Baker hopes that one day there will be a memorial on the Texas A&M campus for those Aggies still missing. “I’ve always envisioned a memorial on campus. A place where you could come reflect on what they did and who they were … I think it’s very important for us here at A&M to have that, and for the families too, knowing that they are remembered together. That they’re missing an action, but that there are people still thinking about them, reflecting on them and using their story today in their life.”

To date, Baker and the team have compiled a list of more than 200 Aggies missing in action. Their new project is putting together a list of Aggies who were in prisoner-of-war camps. So far, they have found 123 from World War II.