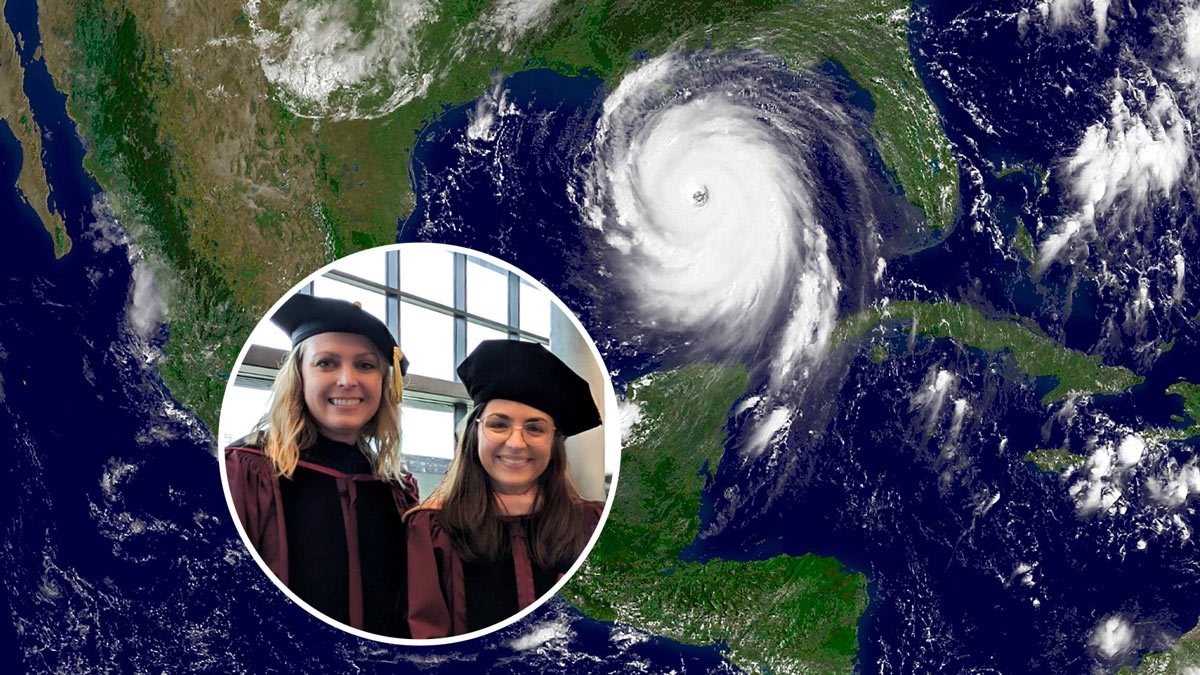

Abbey Hotard ’19, ’23 was just a kid when she and 1.2 million other Americans left New Orleans before Hurricane Katrina. Just over an hour northwest of New Orleans, Ashley Ross ’03, ’10 worked on her political science thesis at Louisiana State University (LSU) in Baton Rouge. Neither were prepared for what happened the day after Hurricane Katrina’s landfall on Aug. 29, 2005.

“You go to sleep thinking this hurricane’s going to miss us and wake up the next day in the middle of a disaster,” Ross, now an associate professor for the College of Marine Sciences and Maritime Studies at Texas A&M University and a researcher for the Institute for a Disaster Resilient Texas, said. “Baton Rouge’s population had doubled in size overnight from the people who had to leave New Orleans.”

Within 24 hours, Hotard’s hometown was flooded. Over 70% of the city’s occupied housing units were underwater. Thousands of New Orleanians found themselves stranded and remained displaced months later.

Hotard, who is an assistant professor of marine and environmental sciences at the University of South Alabama, said her experiences then and in the years after fostered a sense of resistance spurred by the disconnect between her lived experiences and the conversations taking place at the local and federal levels surrounding those impacted by the storm.

Personal experiences from living through Hurricane Katrina inspired both Ashley Ross ’03, ’10 and Abbey Hotard ’19, ’23 to work on coastal resilience research.

“Not too long after Katrina, I was studying for a college prep exam, and one of the essay prompts was a question on whether the city of New Orleans should be allowed to be rebuilt,” Hotard shared. “It was jarring. I was extremely frustrated that I was being asked to justify the existence of my home.”

It sparked her passion for coastal resilience research that would connect her with Ross 12 years later, just as Hurricane Harvey made landfall in Texas. Before that meeting could be possible, Ross had to discover disaster science.

From Political Science to Disaster Science

Ross didn’t realize it when she was studying political science at LSU, but her graduate studies were paving the way for her career in disaster relief efforts.

Ross finished her master’s in political science at LSU in 2006 and earned her doctorate from Texas A&M in 2010. She loved the ties between people and democracy, a passion instilled by her patriotic grandmother, who served in the Coast Guard during World War II.

Ross believes that local governments are the key to helping people have a good quality of life. She began studying democracies in Latin America. However, deteriorating field research conditions in Mexico prompted her to redirect her focus domestically toward Gulf Coast communities, just around the time of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010.

“Based on what I learned about personal well-being and local governance, I pivoted my focus on how local governments in the U.S. deal with environmental crises and disasters,” Ross said. “That led me to this concept of resiliency, which deeply resembles the nature of democracy – messy, complicated, but incredibly promising.”

I pivoted my focus on how local governments in the U.S. deal with environmental crises and disasters. That led me to this concept of resiliency.

Ross has since joined the faculty and is a fellow for the Chancellor Enhancing Development and Generating Excellence in Scholarship Program. She mentors several graduate students and is the faculty adviser for the Ph.D. program in marine and coastal management and science.

“Never in my wildest imagination would I have thought I’d be a professor at Texas A&M. Being able to join the faculty in the College of Marine Sciences and Maritime Studies is an important aspect of my career because it has allowed me to do resilience research and mentor the students becoming the next generation of thinkers about these things – the professors, researchers and practitioners. That’s really one of the most exciting parts of my job,” Ross said.

It’s also how Ross met Hotard in 2017.

Humanity in the Wake of Harvey

Following graduation from LSU with a bachelor’s degree, Hotard was interested in learning how to research community resilience to environmental changes in her home state of Louisiana. She connected with Ross through email to learn more about the master’s in marine resource management, now part of the College of Marine Sciences and Maritime Studies. After an interview with Ross and a tour of Texas A&M’s Galveston Campus, Hotard was ready to move to Texas.

As Hurricane Harvey approached the Texas coast in 2017, Ross reached out to Hotard to make sure she was prepared for the storm.

Abbey Hotard ’19, ’23 was Ashley Ross’ first doctoral student in the new marine and coastal management and sciences Ph.D. program.

In August 2017, Hotard was unpacking boxes in her new apartment as Hurricane Harvey approached the coast. Ross called to make sure she was prepared for the storm and asked her to join her in conducting fieldwork on community resilience in the wake of the storm.

“It’s one of my first distinct memories of Dr. Ross that truly demonstrates who she is and what matters to her,” Hotard said. “As soon as I got to Texas, she’s showing her compassion and empathy for me as a human. Then, I saw her demonstrate that same kindness and compassion over and over while we were doing fieldwork. Having grown up in New Orleans, I’m very aware of what someone might feel like in that situation. It was heartening to be able to translate their experiences into scientific data that will benefit that same community in the future.”

In 2019, Hotard finished her master’s program. Then, in 2020, she became Ross’ first doctoral student in the department’s new Ph.D. program. That following year, Hurricane Ida made landfall on the 16th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina.

Dr. Ross had given me the words to understand something I’d felt all along through the science of resilience … Her influence is integrated into every part of my career path.

“There’s a lot to unpack with Hurricane Ida making landfall on the anniversary of Hurricane Katrina and impacting the same region. I deeply understood from a personal place the cultural and emotional resolve of the people of New Orleans after Katrina,” said Hotard. “Dr. Ross had given me the words to understand something I’d felt all along through the science of resilience. I was empowered to capture stories, distill them using scientific methods and turn that work into something I’m proud of because of what I’d learned working with her during Hurricane Harvey. Her influence is integrated into every part of my career path.”

Resilience is really about the idea of being able to be flexible or adaptive and using the social, financial and community resources available in the wake of a disaster.

Mutual Admiration

Ross says much the same about her own faculty mentors in Texas A&M’s Bush School of Government and Public Service. She credits them with her success as a researcher. Their influence boosted her confidence in communication and science. She explained that their compassion and authenticity helped inspire her own approach to mentorship.

“I try to make sure all my students know that I recognize them as individuals and that I care about what is going on in their lives in addition to the work they are doing,” Ross said. “I definitely got that from my mentors. They never hid the fact that they’re real people, and they were extremely generous with their time and compassion.”

Ross also credits Hotard with making her a better teacher and mentor.

“Abbey would not shy away from giving me constructive criticism,” Ross laughed. “She wanted to be challenged in the classroom, and now I constantly question myself: would Abbey think this is sufficient or challenging enough? It was amazing to watch her through her master’s program, and I’m so grateful she came back for the Ph.D. program. Abbey’s work exploring how people are adapting to environmental conditions today is really innovative and important.”

A World of Difference

Hotard and Ross look at how people experience natural and manmade disasters to reduce community risk and improve disaster preparation and resilience.

“Risk is the harm you think that will come to you if you’re thinking about it from a personal standpoint, such as the capability to leave before a hurricane or health conditions that might limit your response in an emergency,” explained Ross. “While resilience is really about the idea of being able to be flexible or adaptive and using the social, financial and community resources available in the wake of a disaster. It covers any event that shocks your life, from a disaster to an economic recession or personal loss.”

Interactive Data from the Institute for a Disaster Resilient Texas

Texas A&M’s Institute for a Disaster Resilient Texas (IDRT) has interactive online tools to help individuals, communities and governments evaluate community risks. Users can assess their homes for fire and flood risks, explore the economic impacts of storm surge in Galveston Bay and more.

Learn More About IDRTNearly half of the world lives in coastal areas. These regions face rapid ecological changes and complex natural disasters. Communities impacted by disasters like Katrina may take decades to recover. Improving risk management and resilience in these communities can reduce the lasting effects of disasters. The risk isn’t confined to hurricanes. The recent fires in California are another example.

“We know that not every individual in that population experiences environmental crises, hazards or disasters in the same way, nor do they have the capacity to,” Ross said. “What they think about their personal risk, or changing environmental conditions, or storm activity, or how connected they are to their government all matter. Improving our individual awareness and understanding helps improve the way we are ready for what the future is bringing.”

Nearly half of the world lives in coastal areas. These regions face rapid ecological changes and complex natural disasters.

Ross and Hotard work in the same research areas, but they have different focuses. Ross keeps pursuing her passion for political sciences by exploring how social identities drive what people think about disaster risk and how they are resilient. Meanwhile, Hotard continues to study adaptation decisions such as relocation or retreat, as well as experiences with disaster recovery effects of relocation during disasters and the aftermath of retreat. Their special bond and shared goal of helping ensure coastal communities will benefit from their work have kept them friends, colleagues and research partners.

“It blows my mind to this day that I was in grad school just down the road from Abbey while she was experiencing Hurricane Katrina as a kid,” Ross said. “Though we experienced it in radically different ways, it gave us common ground to develop our personal and professional relationship.”