“This final toast is to Lt. Walter Stone, or Buster. He was a hero who made the ultimate sacrifice to protect his friends, keep his family safe so that we could all live in freedom today. It is to him, and to men like him, who we owe a debt of gratitude that can never be fully repaid. But we must try. To Buster.”

This toast was given by Tristan Krause as an example of the many he has given at the resting places of former missing in action (MIA) American soldiers who have finally been found and can be brought back home. A Texas A&M University Ph.D. candidate and historian who has made it his life’s work to recover these missing soldiers, Krause exemplifies public service and what it means to give back to those who have given their all.

There are over 80,000 American soldiers MIA from conflicts spanning World War II to modern day, which means 80,000 families are also waiting for the return of their loved ones. But these veterans have not been forgotten. Krause and many others are tirelessly working to recover these men and women, a fundamental promise the U.S. makes to its service members.

“This is a mission that America takes incredibly seriously, and has done, arguably since the Civil War,” Krause said. “If you make the ultimate sacrifice, and you go and sacrifice yourself for your country abroad, America owes you something. It is the nation’s obligation to go and bring you home, and part of that is to honor past sacrifice and think about the costs of war, because in many respects, these 80,000 people still missing are symbolic of the fact that wars don’t end when the shooting stops.”

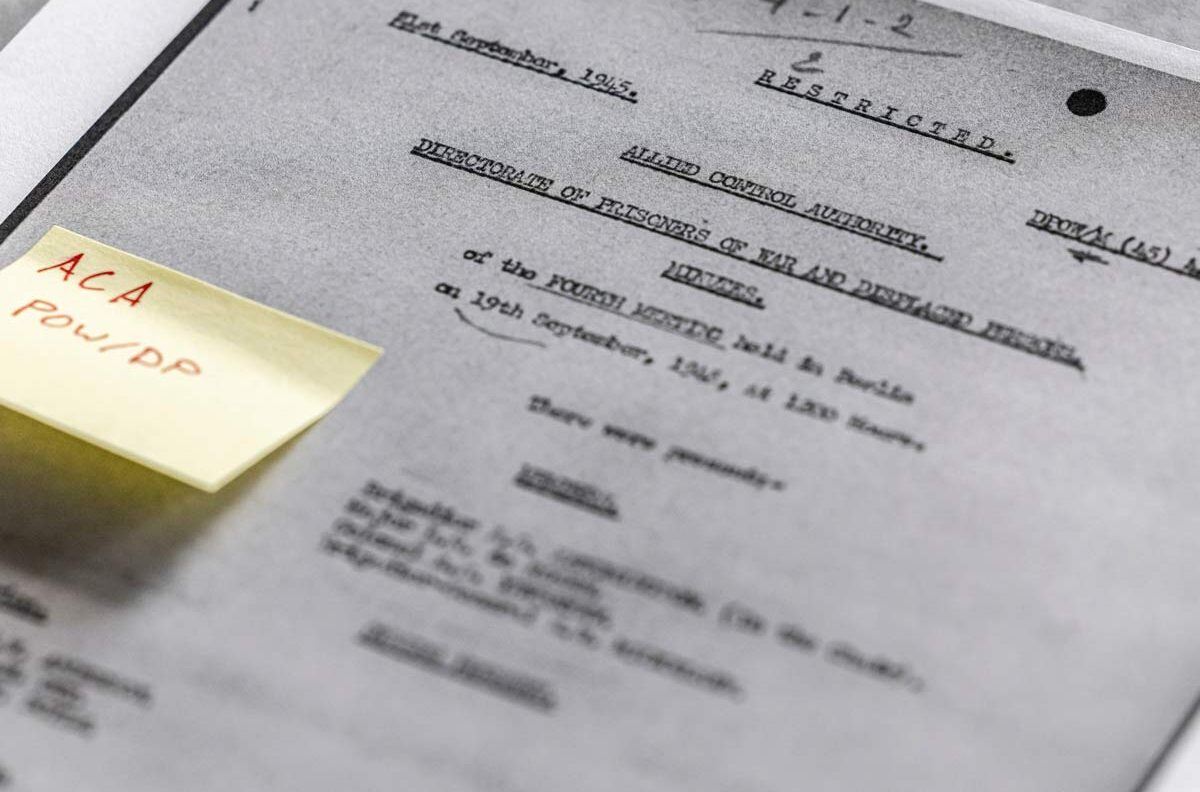

In order to carry out this mission, organizations like the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA) conduct searches in locations such as battlegrounds, crash sites and soldiers’ other last known locations. Through the tireless work of the DPAA, thousands have been recovered and identified.

During his toast to Lt. Walter Stone, Krause shared stories about not only Stone’s service during World War II, but also his family and those who loved him. After 76 years, Stone was finally located in 2017 in a French forest. He was buried with honors on May 11, 2019, just days after what would have been his 100th birthday. He was buried next to his mother, who never gave up hope that he would be found.

Where History Meets Selfless Service

Krause became connected with the DPAA while completing his undergrad at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, a partner of the organization. While working toward his degree and trying to decide how he would use it in his career, he always remembered the principle of public service his parents had instilled in him throughout his childhood. When he found the DPAA and went on his first mission abroad to search for a missing soldier, the pieces clicked, and he knew that he would spend the rest of his life in this work.

“I went first to France, and that was a P47 fighter pilot crash. I believe it crashed in 1943. That was my very first time. And it was 2018, I was an undergraduate, and I wasn’t really sure what I wanted to do. And I remember going on that dig site and finding a bullet, and thinking, ‘Oh, OK, this is where we should be. We’re in the right spot.’ All this historical research you’ve been doing for months, all this prep work, has come down to this moment where this slight indentation of this French forest is actually the fighter pilot’s grave that we haven’t found for 80 years, and we’re about to bring him home. That was the moment I was like, ‘OK, I need to do more of these.'”

After earning his undergraduate degree in history, Krause knew he wanted to continue his education, diving deeper into historical research in order to be as effective and helpful as possible on more missions.

He learned about Texas A&M through an undergraduate mentor who had recommended four different options for schools that would foster Krause’s desire to use his love of history for public service.

Texas A&M has been a perfect home for Krause to combine his love of history with a strong sense of service. He and his colleagues are tirelessly working to recover those still missing, a fundamental promise the U.S. makes to its service members.

“It’s not like other universities,” Krause explained. “When it says service, it really does mean it. It’s baked into the Corps of Cadets here. It’s baked into the campus and its traditions. It’s baked into the fact that we had more commissioned officers go off and fight in World War II than any other school besides the service academies. This is really not just history. It’s a tradition at A&M, and you can tell it means something to the students here, and to the faculty and the graduate students as well. And so, this makes sense as a place to go and study past sacrifice and bringing the fallen home.”

Now Krause is in the process of earning his Ph.D. from Texas A&M in the College of Arts and Sciences. He recently secured a grant from the German Academic Exchange Service that will allow him to conduct research for his doctoral dissertation at the University of Freiburg in Germany, regarding the search for post-World War II MIA American soldiers in Germany. He’s grateful for how Texas A&M has set him up for success in both his education as a historian and his pursuit of meaningful public service.

Uncovering the Truth, One Search at a Time

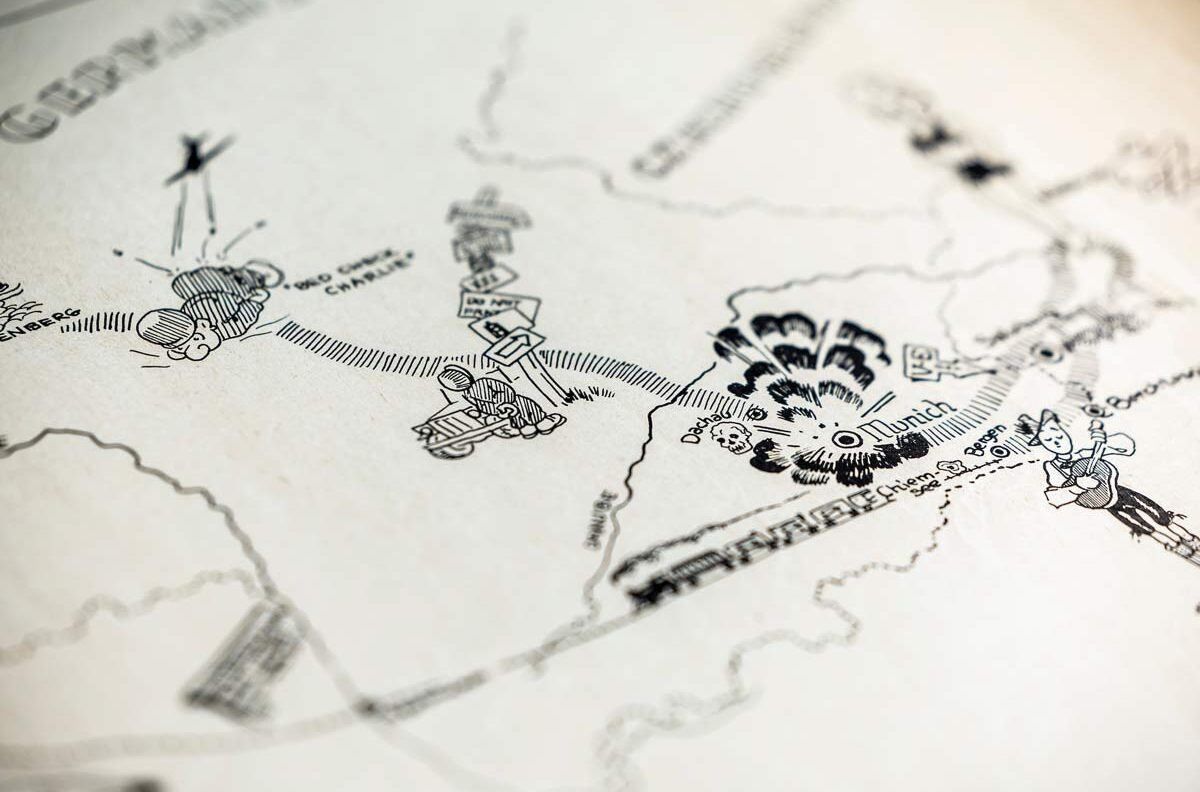

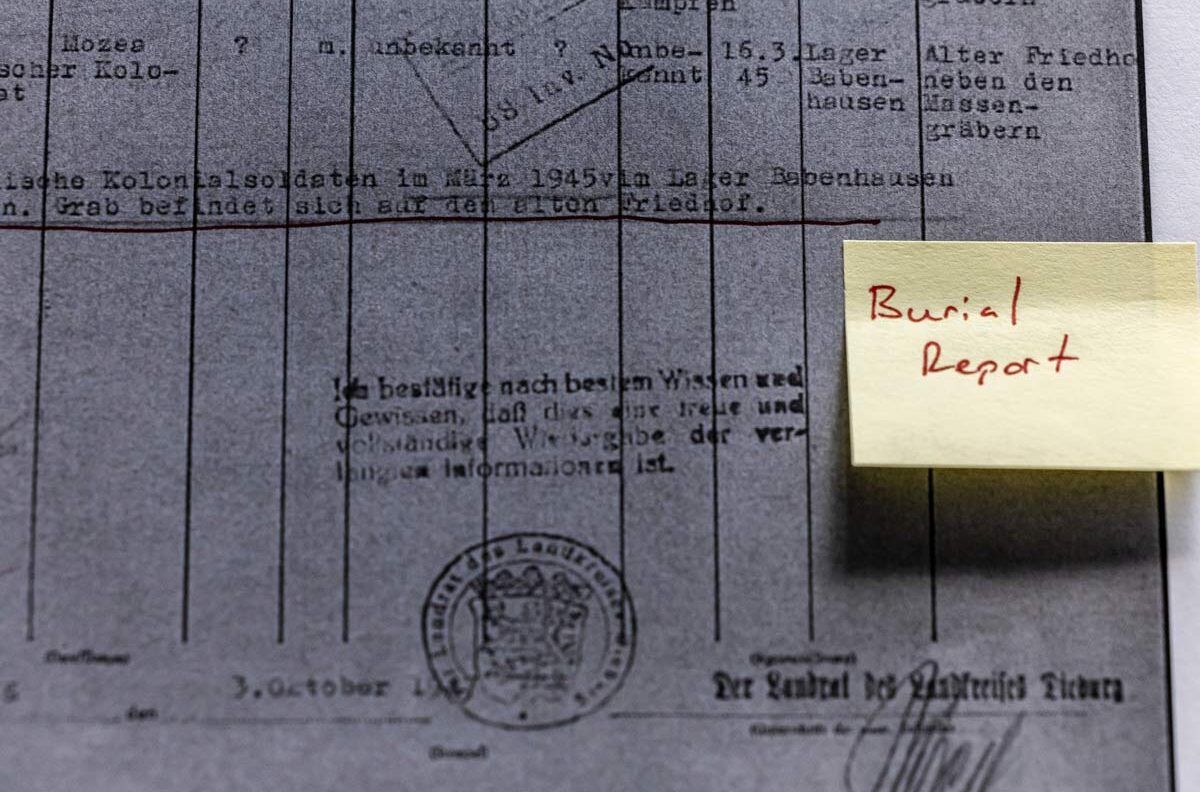

Since his first mission, Krause has gone on nine more, including to Italy, Belgium and Germany. As a historian working on these digs, his role begins before the team even arrives at the site. Before leaving home, Krause does extensive research on the events and factors that led up to the exact moment a soldier went missing. These include who was there, where the regiment was, what direction the aircraft would have been flying, who could have seen something, what the specific mission was and other important pieces of context.

“You have to have an idea of where to start looking. And so the historian’s job is to go through and do that archival research, to find those sources, to find those eyewitness accounts, to find those reports that might give us any sort of advantage … Detective work is a good way of thinking about it. And so that’s the historian’s work. Before any shovel hits the dirt,” Krause explained.

Photos by Abbey Santoro/Texas A&M University Division of Marketing & Communications

And once he’s at the site, his job continues. As each piece of possible evidence is found — a bullet, a piece of metal from the aircraft, a patch of cloth, etc. — Krause uses all the research he’s done to help determine whether the artifact is a piece of the soldier’s final moments, and if so, what part in the story it plays, and how it can lead to the exact location of the soldier’s remains.

But his responsibilities not only involve research and evaluation of evidence — he is on the ground with the rest of the team, digging and sifting through mesh screens for days.

A day on site begins with the area being gridded into sections called “units.” Dirt from each unit is then put on a tarp to ensure that it does not mix with dirt from other units, and if something is found, the team knows exactly where it came from. The dirt is then divided into buckets and sifted through, one mesh screen at a time, very carefully in order to distinguish evidence or osseous remains from twigs and rocks. When a piece of evidence is found, it goes through Krause or one of the other historians for identification. If human remains are found, the focus shifts to the unit in which they were buried.

“There are long days,” Krause admits. “But when you find something, when it’s rainy and cold and you’re sore and you’ve been mattocking for four days straight and your back’s hurting, and then you see a lighter in the screen, or you see a tooth, and you know that tooth is one of the best sources of DNA for getting a match. And you know that you’re that much closer to bringing somebody home.”

Searching for Those Who Sacrificed All

During the harder days, Krause continually remembers to put the challenges in perspective of the sacrifices that the men and women he’s searching for have made.

“It’s really easy to sit there and be like, oh, woe is me. I worked really hard. My hands are really killing me. My back is sore. I’m soaking wet. But then you think about, well, the young man I’m looking for is 25 years old and died in a plane crash because he was shot down and he took off from Tunisia, where it was 140 degrees and they had to sleep under their wing tips at night, things like that. It really puts it into perspective.”

Every service member Krause searches for has given everything they have — time with family, a long, peaceful life, their future career and even the assurance that they would be laid to rest in their home country — for the sake of keeping their fellow Americans safe.

The mission of bringing home the fallen from past conflicts and giving them a name, and then having the family be able to have that closure, felt like the best use of my history skills as a historical researcher… The way I’ve always phrased it is, ‘Humanities in action.’ And A&M is a place that really fosters that.

Krause also thinks of the families who have been waiting decades for their loved one to finally come home. In the case of Stone, whom Krause gave a toast to, the next-of-kin was his nephew, who Krause says, “saw his dad hug his brother [Stone] on the train station in a rural community in Alabama and send his brother off to war and never see him again.” Stone’s brother had since passed away, as well as his mother, but the remaining family now has the peace of knowing that their relative is back home. And he’s buried next to his mother, who always believed he would return someday.

Digging into Stone’s background and the histories of all the other fallen soldiers Krause and his team search for help him constantly remember the humanity of the missing service members. They are not just bones in the ground, but people who loved and missed their spouses, had dreams of what they would do once they returned from war, and knew and accepted the chances they were taking when they deployed to protect their country.

Having this mindset means that Krause feels the emotional impact when remains are discovered. After months of diving into a person’s life, all the way up until the moment they died, finally discovering their remains is both a heavy emotional hit and a big relief.

Krause recalls the first time he encountered the remains of an MIA soldier. “I called our anthropologist over, and he said, ‘Oh, we are going to bag that. That might be him.’ And I actually sat down. As a historian, it’s like, oh, this is lived history. This is part of World War II’s history. And I picked out what is probably part of our missing pilot out of my screen. And that might have been the only part that got put back in the coffin and identified. But it was enough. It’s enough to say we know what happened, and here he is. We’re going to put him back in and bury him. And so I literally did sit down. It was pretty overwhelming.”

Honoring the Past While Looking to the Future

In his work as a historian, something that has become very apparent to Krause is that history carries forward into the lives and world of today and the future. Not only are soldiers who gave their lives in battle missed and remembered by their friends and families, but their sacrifices build into a story of tragedy, perseverance, kinship and selfless service. This story helps us move into the future with wisdom, knowing the effects of conflict, as well as gratitude for the opportunities we have in this country that were won on the backs of those who made the ultimate sacrifice for our freedom.

Those in the military recognize this more than most. “Today, we have units from these MIA crew members or servicemen that we’ve looked for that are still alive today … And I guarantee you, they care about their unit’s history and their unit’s lineage. I know that [one] unit — which occasionally flies into College Station during training — had its final reunion of World War II veterans two years ago, and it had four remaining pilots in World War II, just four. But even after they pass away, that unit and those modern pilots and crew members are still going to care about their lineage. So that just shows you, in one snippet, that within the modern American military, this matters more broadly.”

Through his position as a historical researcher, Krause has found a way for his skills to serve as a force for good. And he’s grateful for the opportunity to learn and grow at a university that has that same purpose.

“The mission of bringing home the fallen from past conflicts and giving them a name, and then having the family be able to have that closure, felt like the best use of my history skills as a historical researcher. As somebody out in the field, as a historian on these archeology sites — that felt like the way it should be. The way I’ve always phrased it is, ‘Humanities in action.’ And A&M is a place that really fosters that.”