NASA Papers Acquired By Texas A&M Give Insight To Aerospace Medicine Research

Three Texas A&M University students have been combing through former Chief Scientist of NASA Dr. John Charles’ collection, containing glimpses into the history of aeronautic medical research.

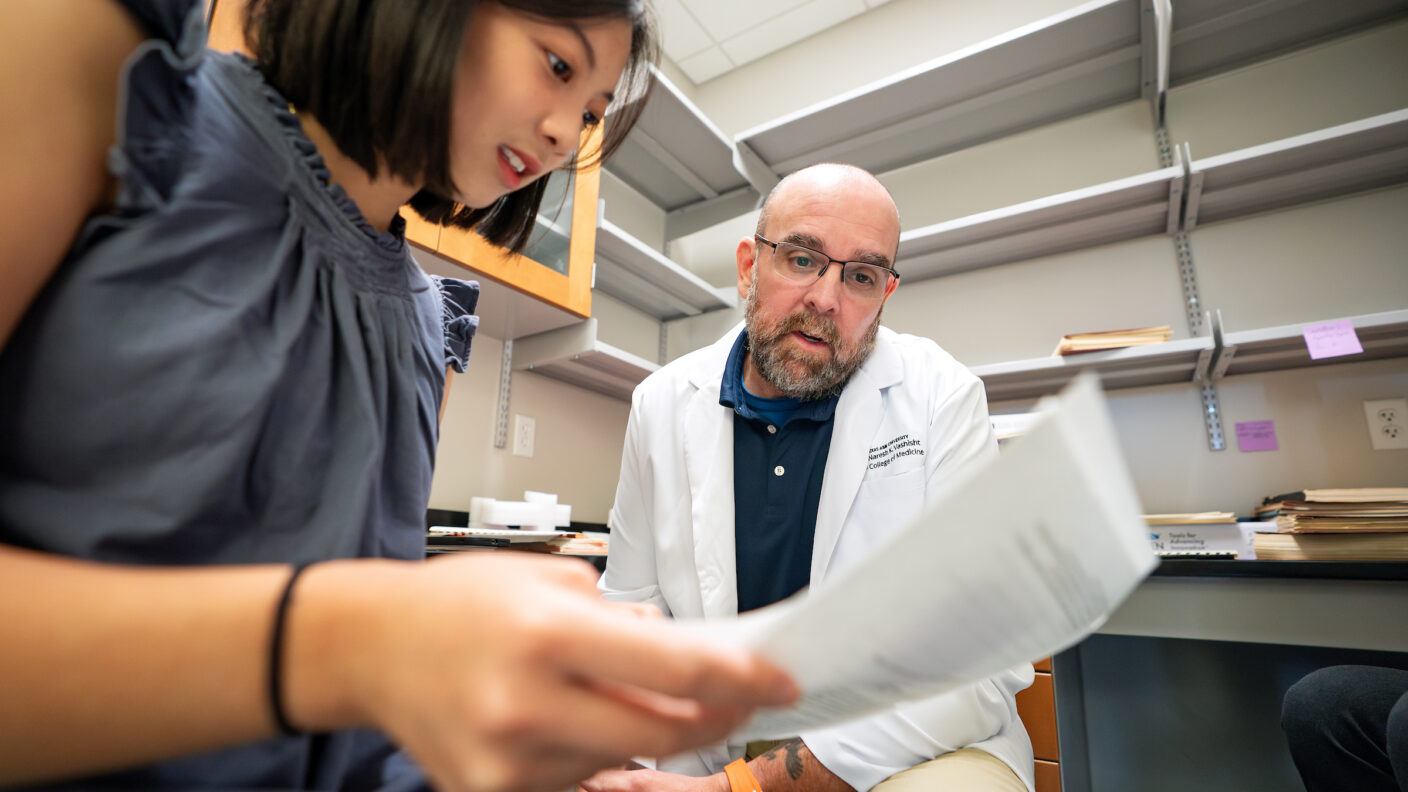

Chemistry senior Madelyn Pham looks through materials from the collection that once belonged to Dr. John Charles, former Chief Scientist of NASA’s Human Research Program. Charles’ collection was recently donated to Dr. Jeffery Chancellor, director of the Aerospace Medicine Program at the Texas A&M University College of Medicine.

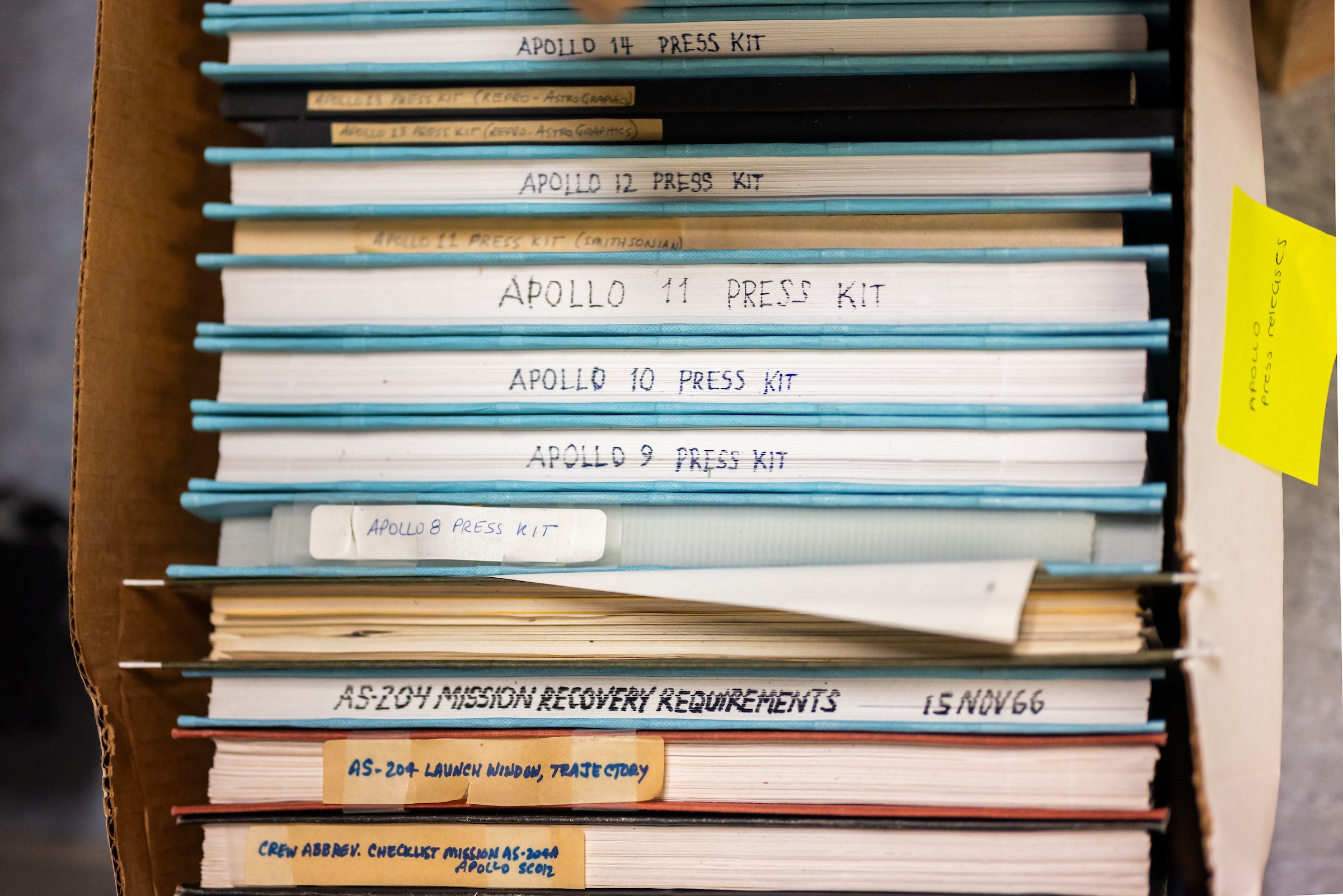

In a lab at Texas A&M University, nearly 1,000 pounds of VHS tapes, declassified NASA documents and photos are neatly stacked on floors. Each piece, from footage of the Apollo 8 mission in 1968 to photos of astronauts eating breakfast, tells a story of a time long ago.

The documents were meticulously kept by Dr. John Charles, former chief scientist of NASA’s Human Research Program. The collection holds decades of historical and scientific importance from his time at NASA. Along with working as the mission scientist for notable space shuttle flights STS-95 and STS-107, he played a pivotal role in the NASA Twins Study that compared astronaut Scott Kelly with his identical twin Mark Kelly, providing key information on the genetic, physiological and cognitive impacts of extended space missions.

After Charles died in 2022, his collection was given to Dr. Jeffery Chancellor, director of the Aerospace Medicine Program at the Texas A&M University College of Medicine, who worked with Charles. While it may seem like a herculean task to comb through each document, VHS tape and file, three Texas A&M students, Wyatt Sprague, Madelyn Pham and Caroline Anderson, rose to the occasion under Chancellor’s guidance to catalogue each piece.

“At NASA, they had a saying: Xerox everything,” Anderson said. “During an interview in 1998, Dr. Charles said that was one of the difficulties in working with Russia. If he handed them an unfinished paper, they would keep it and throw away all revisions. At NASA, they kept everything. He definitely took that NASA philosophy to heart.”

Pham and Dr. Jeffery Chancellor sort through Charles’ materials, which include nearly 1,000 pounds of documents, photos and VHS tapes.

Charles championed medical research efforts of all kinds. Some notable items from his collection include DVDs of Buzz Aldrin being measured before and after his flight, astronauts learning to maneuver in prototype suits, and videos of the original Apollo 11 mission.

Chancellor worked with Charles when he was the chief scientist of the Human Research Program at NASA and on the Manned Orbiting Laboratory, the top-secret Air Force space agency established in the 1960s. Charles was also the principal investigator on some flights with Dr. Bonnie Dunbar, retired NASA astronaut and professor of aerospace engineering at Texas A&M.

“Dr. Charles lived and breathed space,” Anderson said. “From what we saw from the papers, he would spend his free time emailing colleagues doing statistical games. He would calculate what percent of astronauts were married, divorced, and how many have flown on space flights. He was truly cataloging everything. There’s not that many minds that are that curious.”

While some information may be outdated by today’s standards, other documents remain relevant. Chancellor said he was particularly interested in Charles’ research on the shift in body fluids in astronauts before and after their trip.

“In microgravity, the absence of gravitational pull causes bodily fluids to shift upward toward the head,” he said. “But it’s not the fluid shift itself that poses the greatest danger, it’s the cascade of effects that follow. Spaceflight Associated Neuro-ocular Syndrome, or SANS, is one such outcome, and astronauts have even developed complete clotting of the left internal jugular vein during missions, which is a major health concern. Dr. Charles worked on early countermeasures using lower body compression garments to push fluids back down, counteracting the abnormal distribution seen in space.”

Compared to other sciences, aerospace medicine can be difficult to study due to the smaller sample pool of astronauts. Due to this, aeronautic research will often research previous cases or use prior data, making Charles’ research important both historically and scientifically.

Dr. Charles lived and breathed space. From what we saw from the papers, he would spend his free time emailing colleagues doing statistical games. He would calculate what percent of astronauts were married, divorced, and how many have flown on space flights. He was truly cataloging everything.

“For some of this research, you can look back and see what was important back then and what was prioritized,” Pham said. “As technology advances and research goes on, we may need to look over everything again, but it’s definitely still cool to see.”

Figuring out how to sort the collection was no easy feat. Sprague said the team started by devising a strategy — organize each piece on the macroscopic level, then sort each category by smaller details.

“Basically, we categorized items into what they are and separated personal research and personal collections. He collected a lot of magazines and films. Now, we’re going to sort through more minute differences between each piece,” he said. “If this was all stored on a hard drive or USB stick, it could easily get lost or corrupted. There’s a lot to learn here and shows why it’s so beneficial to have this physical medium in research.”

Ultimately, the team plans on making the information accessible to researchers, medical students and anyone with curiosity by donating the collection to the Texas A&M University Libraries.

“This whole project demonstrates the value of aerospace medicine. You have biomedical sciences, chemistry, nuclear engineering and physics all working on solutions. It makes A&M unique in this way because we can tie our research to the medical school and engineering,” Chancellor said. “We could get a valuable collection assembled here at Texas A&M.”